03 Jul V Cycle – What Remains of the Development

Fifth Cycle

What Remains of the Development

I was born in Puglia and I am extremely fond of my land. I spent my childhood there and I have returned many times. My mother was from Martina Franca, a town not far from Taranto. This series stems from the memories back then to the memory that followed.

When I was a child, Taranto seemed to me like a strange city: two seas, a swing bridge, a pile of floating golden stones that divided the small sea from the open sea. Surrounding this was the colour green, coloured by the farms and olive trees. And then the fishermen with their wooden boats. Those were the sweet memories of Taranto.

I hadn’t returned for many years, even if I had spent most of my summers in Puglia. In fact, it was in 1964 during one of my holidays that my uncle suggested we take a trip to Taranto. I found this city had transformed, it was almost unrecognisable, chaotic. Cars and motorbikes crowded the streets, as did the sounds of engines and hooters. A chaotic city. You couldn’t detect the scent of the sea anymore. It had been one year since Italsider, Italy’s largest steel producer, had begun manufacturing. I returned to Taranto in 1978 as a young architect, for work-related reasons. As I set foot in the city I felt anxious and disoriented. What was the sense of those areas so close to the steel mill?

I couldn’t comprehend. Perhaps I should have been prepared, I knew very well what had happened and what was happening and maybe I could have imagined what happened consequently to that city, to which I returned towards the end of the 90s and again at the beginning of the 2000s. I came from Martina Franca by car. It was evening. I stood watching from the top of a hill that descended towards the sea. Taranto didn’t exist anymore. I saw hell made up of fire and smoke. The largest steel mill in Europe had eaten up the city, the countryside and drunk the sea. I walked back to my car and turned back. I didn’t want to erase my memories. They had to stay there. Now I just had to study in order to understand, activate my memory.

I began to think of the series “What remains of the development”, to the largest steel mill in Europe, first Italsider, then Ilva, now Arcelormittal and tomorrow, probably, nothing. I began to work.

Next to the structure two other monsters puffed out poison: the petrochemical plant and the cement plant. Why was there so much fury towards that city? Taranto is the example of what remains of the development. As Pier Paolo Pasolini mentioned, the “development” was to be compared to “progress”. The first focuses on technologies whereas the second, on humankind and their thoughts. As you study the history of Taranto’s development, you get the feeling that there, and I’m not sure how unintentional it may be, an experiment has been carried out: to verify the tolerance of mankind: can one go beyond life for work? In Taranto, people get sick – not only the workers but also the children: respiratory problems, heart problems and tumors.

As a result of the demon-factory 40.000 secular olive trees were cut down. What can stem from such a massacre?

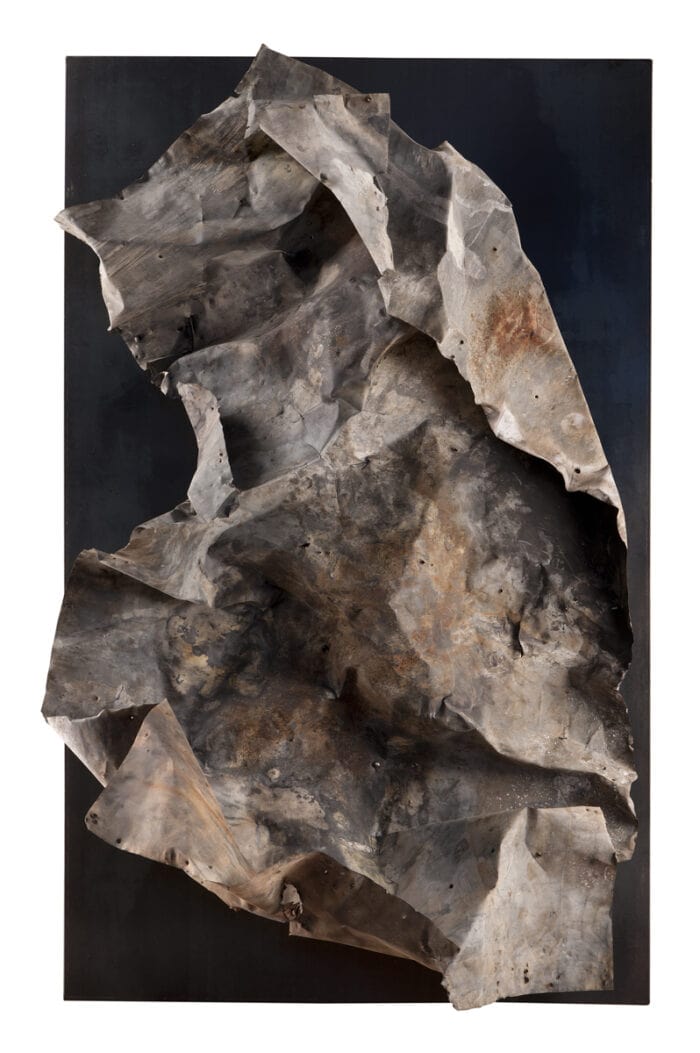

The series is made up of different works. The central one is an installation: “Suits and Steel”.

It’s made up of ten panels each of which feature a lacerated metal sheet, tarnished with oxides and acids and set on fire. These are the suits of the workers who, after their work shift, deposit them in a sort of clearing room before entering the showers.

I treated the metal sheet in such a way as to appear as a rough anthropomorphic drapery to the observer. But also as the elegant, innocent and tormented soul of who wears those suits.

The ten panels have been inserted in just as many oxidised Cor-ten steel chests that represent the workers’ buildings; red like the poisonous powders and built just behind the plant. Other works from the series: “Twelve Sick Papers” and “What Remains of the Development”.